Warning: This post mentions suicide and domestic violence, and may be triggering for some readers.

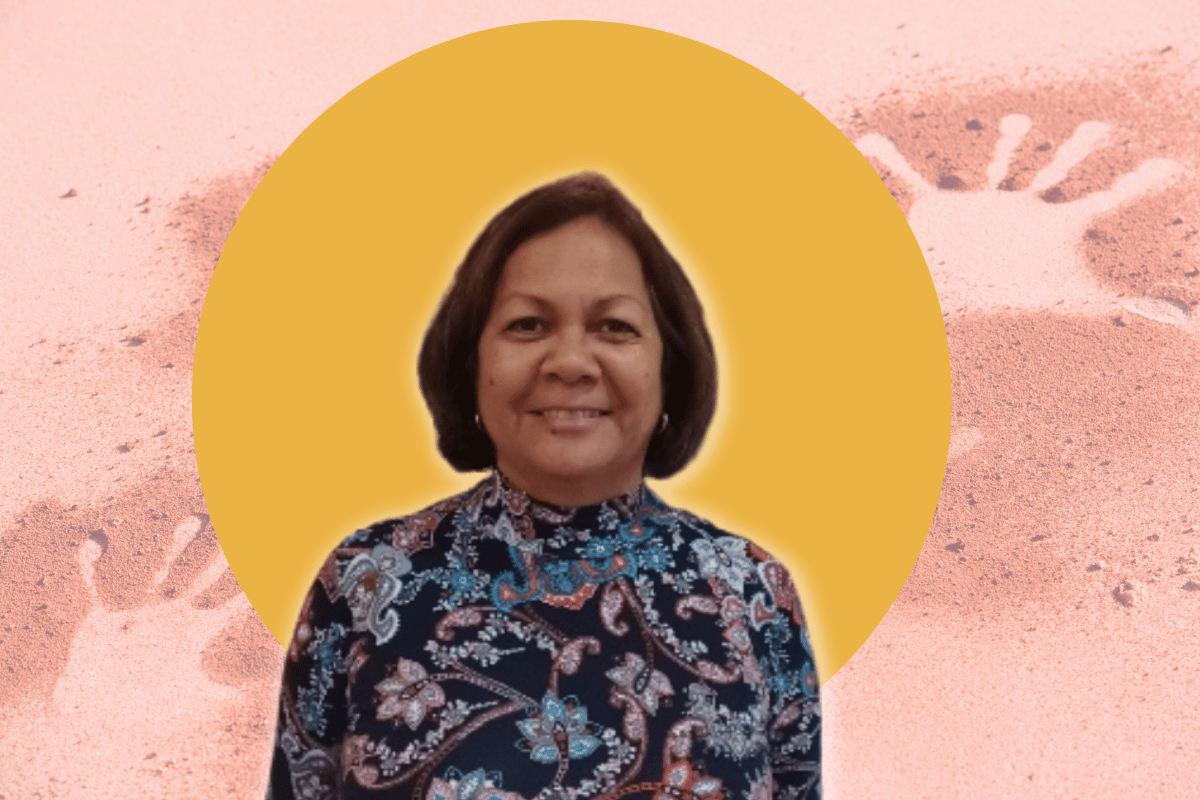

As proud Waanyi/Kalkadoon woman Sandra Creamer reflects on the hardships she has faced, there is one memory in particular that hangs heavily on her words.

After mustering the courage to leave her violent marriage, she found herself at 33 years old, with four children in tow, and "as poor as a church mouse”.

They ate bread and gravy. Their electricity was regularly disconnected. And her car had been repossessed.

“I remember my son needed a haircut, and I just didn't have any money. So my daughter went ahead and cut his hair really short,” Sandra tells Mamamia, her voice cracking.

“When he walked out, it hit me: Is this how broke we are? That I can't even afford a haircut for him?”

It came after Sandra had also been forced to leave her job after suffering discrimination in the workplace.

“Being a single mother, having bills to pay still gets me upset,” she says, apologising for her tears.

“But I thought, I’ve just got to get up. I have to turn this around.”

Indigenous children of the Kimberley tell Mamamia what they aspire to be when they grow up. Article continues after video.

Top Comments