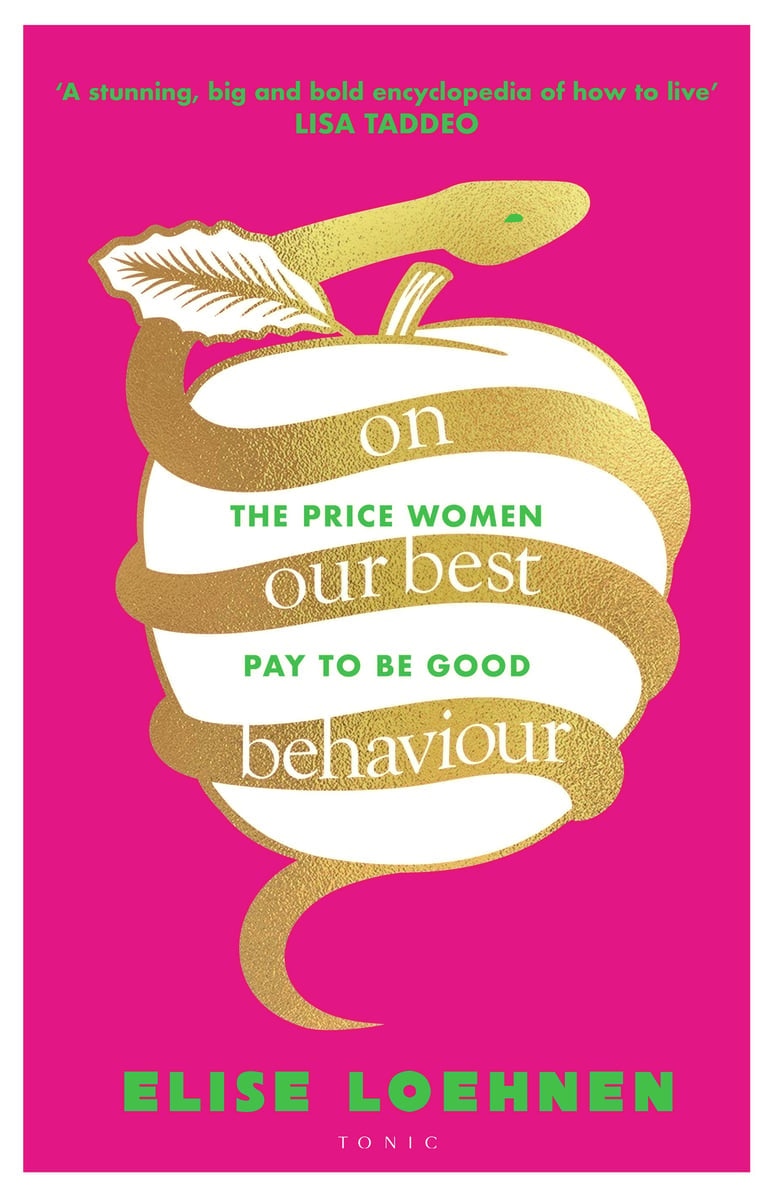

The following is an excerpt from On Our Best Behaviour: The Price Women Pay to be Good by Elise Loehnen, a probing analysis of history and contemporary culture that explains how women have internalised the patriarchy, and how they unwittingly reinforce it.

In late 2019, I hyperventilated for an entire month.

I could not take a deep, complete breath without yawning because, ironically, my lungs were over-saturated with oxygen. Hyperventilation is a classic mix-up between the body and the brain that I had been experiencing on and off since I was in my twenties.

The first time it happened, I went to the emergency room thinking I had hours to live before I asphyxiated and that I needed to be intubated, stat. The doctor advised me it was all in my head and sent me home with a pat on the back and a Xanax prescription. This recent spell was different. I couldn't nap it away. Cutting out caffeine offered no relief. I struggled and suffered, yawning and sighing through meetings, interviews, and meals.

It's a strange experience—to appear to the world as calm and sedate, sleepy really, while contending inside with consuming anxiety. I felt a bit like a duck, paddling frantically beneath the surface, while appearing to glide with little effort on top.

Watch: Elise Loehnen's tips for living a balanced life. Post continues after video.

Top Comments