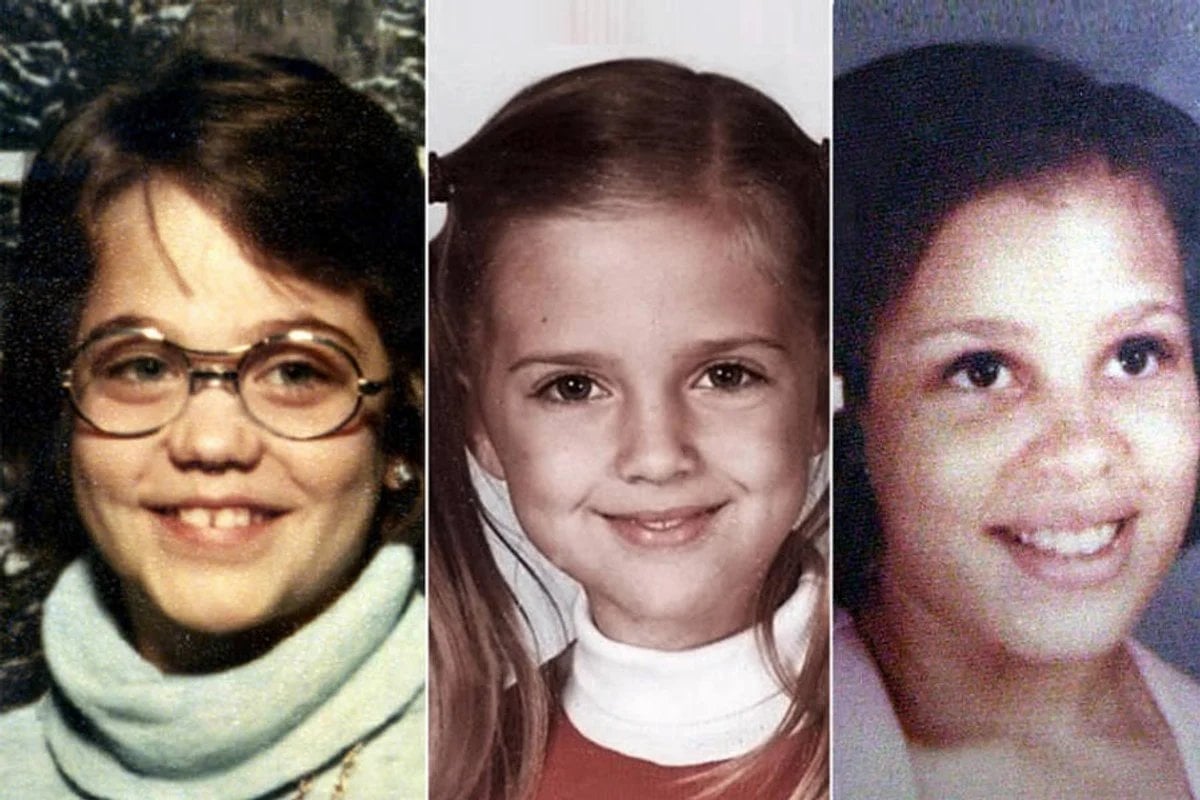

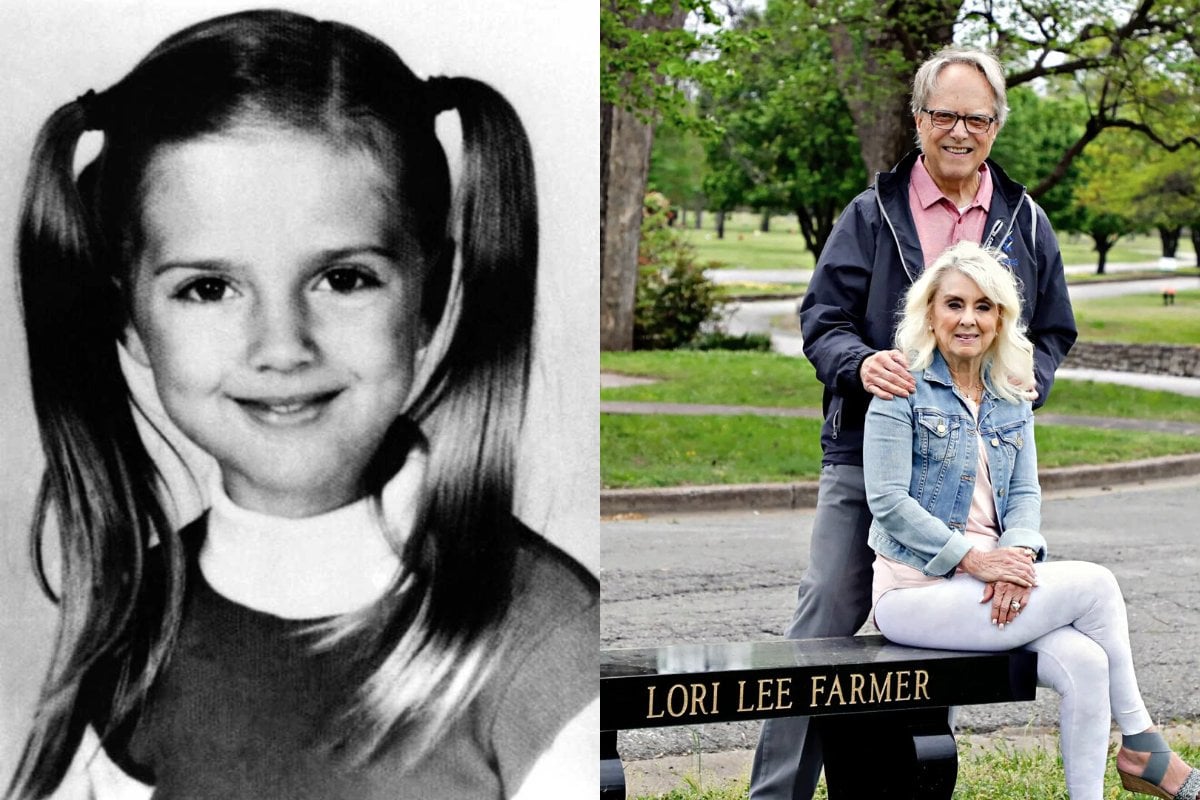

It’s been 46 years since Sheri Farmer hugged her eight-year-old daughter Lori, told her she loved her, and waved goodbye to her as she got on the bus for Girl Scout camp in Locust Grove, Oklahoma. On her first night at camp, Lori was brutally murdered, along with the two girls who shared her tent, Michele Guse and Denise Milner.

Sheri is now 78, but she and her husband Bo haven’t given up on finding out who killed their daughter.

“I promised Lori we would continue searching for justice – and we would do something positive in her memory,” Sheri says in a new interview with People Magazine Investigates, airing July 10 in the US.

Watch the video showcasing the identification of the killer in the 1977 Girl Scout Murders. The post continues once the video concludes.

Lori was the youngest of the Girl Scouts who arrived at Camp Scott on June 12, 1977 for a two-week summer camp. But as the oldest of five children in her family, she was mature for her age, and, her mother remembers, “just a really good oldest sister”.

“I wish I had not let her go,” Sheri told People in 2018. “It was her first time to ever go to camp anywhere.”

Lori, nine-year-old Michele and 10-year-old Denise were assigned to the tent furthest away from the camp counsellors.