God forbid you should see inside the mind of a grieving mother.

Nothing you find there will be tied in a neat bow for public consumption. Nothing will be sturdy enough to be held up to the light for scrutiny from people who are not half-wild with a bottomless grief.

And yet, we all looked inside the mind of a woman who had lost not one, but four infant children, and decided that the fragments of sense we saw were enough to lock her away for life.

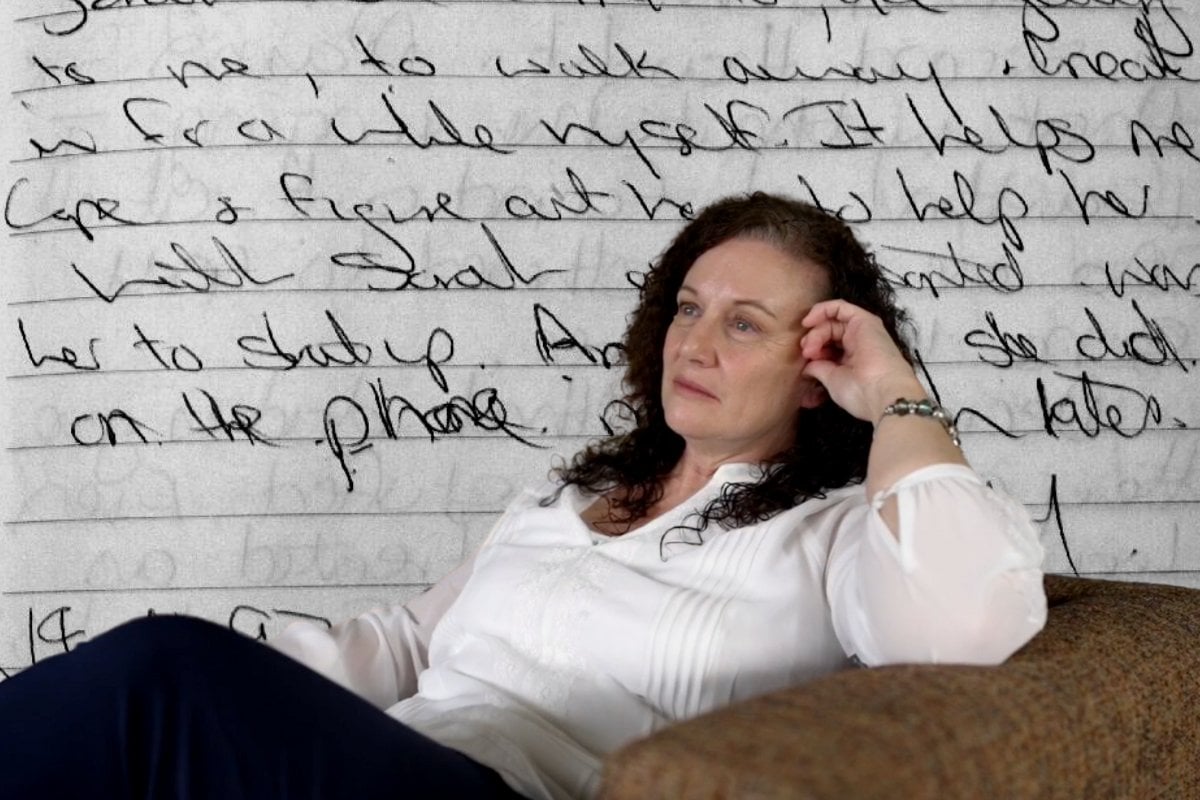

Kathleen Folbigg's diaries put her in prison.

The scientific evidence against Folbigg as she stood trial for her children's murder and manslaughter in 2003 was patchy. And complicated. All four babies – Caleb, Patrick, Sarah and Laura – had died in slightly different ways.

Caleb was only 19 days old. It was ruled as SIDS. Patrick suffered repeated seizures. Sarah and Laura's deaths were the most similar – both little girls stopped breathing in their cots, Sarah at 10 months, Laura at one-and-a-half. But there was no evidence of smothering, no signs of struggle. In the case of Laura's death, there was only a frantic triple-0 call from a mother desperately trying to perform CPR she had learned by terrible necessity, and wailing that she could not lose another.

The details of the deaths themselves were not credible cause for a conviction, and this week, their scientific causes set Folbigg free.

Watch: A statement from Kathleen Folbigg following her release. Post continues after video.

Top Comments